By Neena Bhandari

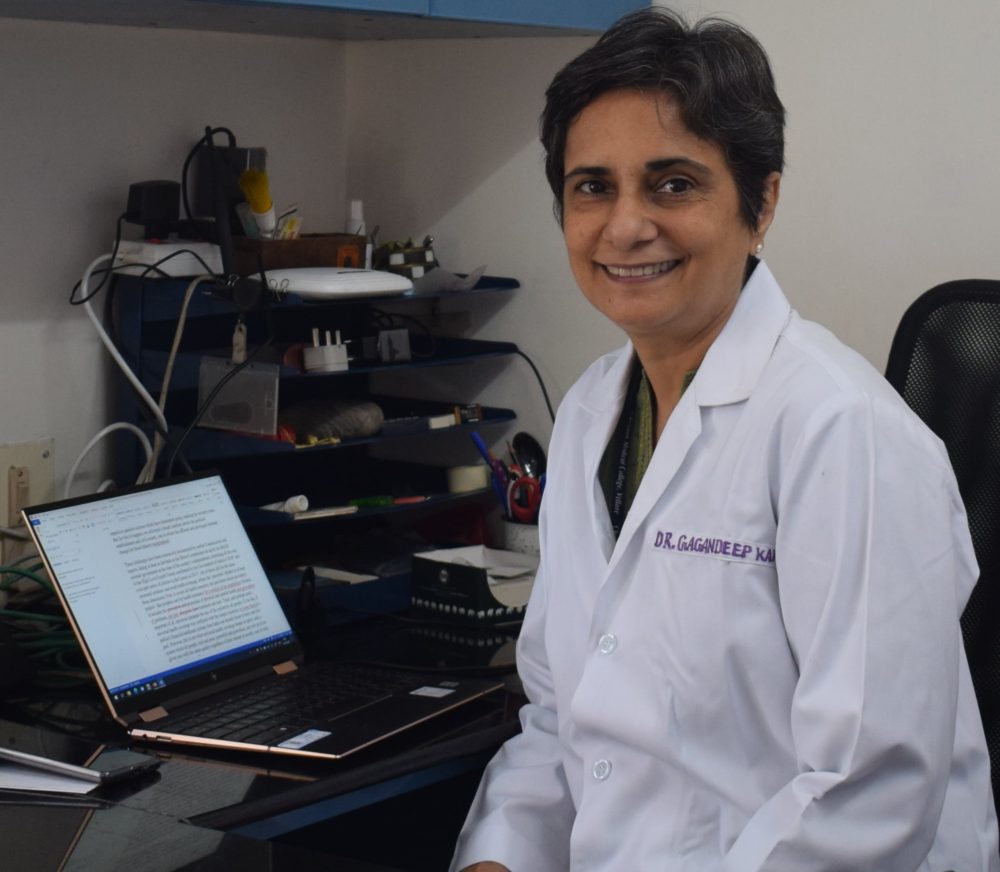

Sydney, 31.08.2020 (SciDev.Net): Internationally renowned for her inter-disciplinary research on transmission, development and prevention of enteric infections and their sequelae in children in India, Gagandeep Kang is the first Indian woman scientist to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. She is a member of the WHO’s Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety.

Currently, a professor of microbiology in the Division of Gastrointestinal Sciences in her alma mater, the Christian Medical College Vellore, Kang grew up in a science-oriented household, reading Isaac Asimov. She attended 10 schools in 12 years as her father, a mechanical engineer in the Indian Railways, was transferred across northern and eastern India.

The frequent transfers taught her to be adaptable and learn outside the classroom. She spent time learning on her own with help from her parents. They would visit mines to understand about minerals and chemicals. Her father would bring home lenses, concave mirrors and Woulfe bottles and they set up their own lab and herbarium.

She believes curiosity and persistence pay. Curiosity allows one to question and there is nothing more fun in life than to be able to answer one’s own questions. Persistence is important because it helps one to learn from failures and move on.

Kang is passionate about improving the health and lives of children and the community. She spoke with SciDev.Net about the barriers she faced as a scientist, her interest in virology and water-borne diseases, the training programmes she has established to build a cadre of clinical researchers in translational medicine, and the importance of vaccines in curbing the burden of infectious diseases on public health.

How important are vaccines in curbing the burden of infectious diseases in developing countries? What would you tell people who are anti-vaccination?

I am in favour of vaccines. Most of the infectious diseases — tuberculosis, typhoid, diarrhoea or influenza — for which we make vaccines are a huge public health problem. If you have a licensed vaccine, which has been tested to be safe and efficacious, and it can prevent an infectious disease, why would you want to experience that disease?

The focus of vaccines has to move from prevention of deaths to prevention of illness. Wherever there is a disease that causes significant morbidity or mortality, we should be looking at making a vaccine. Occasionally, vaccines may have side effects. But by and large those are predictable and manageable. People are anti-vaccine because there is fear of adverse reactions. We need to address their concerns about vaccines being unsafe.

When do you think an efficient vaccine for COVID -19 will be available globally? How hopeful are you about an Indian vaccine for COVID?

There are no guarantees, but the chances are very high that we will know about the efficacy readouts of several products by the end of the year. If vaccine trials are successful, we are looking at bulk supply sometime towards the end of 2021.

Serum Institute of India has multiple vaccines in development. They have started the University of Oxford’s vaccine trials with the first volunteers vaccinated with the first dose in Pune on 25 August. There will be a second dose after four weeks. If this vaccine, licensed to Astra Zeneca, which is in phase 3 shows that the vaccine is efficacious then we will have the vaccine in India very early because Serum is making it already.

Even if none of the Indian programmes winds up being successful, India is such a large supplier of vaccines that many countries will want an Indian partner for the manufacturing of vaccines. I would expect that there would be technology transfers and subsequently vaccines made available for India and from India for the world.

What steered you towards specialising in rotavirus epidemiology and vaccinology?

I was doing surveillance for rotavirus in the community and in hospitals. The community work led us to understand that Indian children responded to rotavirus infection differently to those in western countries. We did not have as much protection, which effectively meant that vaccines wouldn’t work well.

The Indian team was working on two vaccines that were based on neo-natal strains. My work in the community had showed that one of those two strains, which was a vaccine candidate, would not protect from subsequent infection. This was not something the rotavirus community wanted to hear.

I was very much persona non grata in India in the early 2000s. However, I was well accepted overseas. My funding came from international sources, which gave me a great deal of independence. I had built my own lab to look at immune responses to rota vaccines. We managed to publish our data, with some difficulty, in a peer reviewed journal. It turned out that the one vaccine candidate that we had said wouldn’t work, three years later the people who were working on the candidate also found the same thing. At that point, I was accepted into the wider gastrointestinal research community in India.

Why did you choose to specialise on diarrhoea?

I started out studying diarrhoea because it was fascinating that the gut is actually an external environment and an internal environment with many bacteria and viruses in it. I spent years trying to figure out the difference between colonisation, infection and disease.

Nobody was studying rotaviruses to make a diagnosis. I started by working on the diagnostics of rotavirus and then started to look at what are the immune responses and that led to the idea of prevention and of new vaccines.

Water-borne diseases — diarrhoea, cholera, typhoid – are a major public health burden in developing countries. What measures can be taken to redress this problem?

With all enteric infections, the government needs to invest more in prevention. When you invest in treatment instead of prevention, the incidence of disease doesn’t change. A cheap, effective, oral cholera vaccine is available. Why don’t we use it amongst populations at risk?

We have just finished what we call the Rolls Royce of surveillance studies for typhoid. Our model looks at typhoid in the community all the way to hospitalisations and death. We are now doing the cost-effectiveness modelling for the typhoid vaccine, which might be a solution to both typhoid and a collateral benefit of resulting in a decrease in drug resistance. We have a good Indian Typhoid vaccine made by Bharat Biotech. One dose protects for at least five years and it has 80 per cent plus efficacy.

You have been investigating the complex relationships between infection, gut function and physical and cognitive development, playing a significant role in seeking to build stronger human immunology research in India. How easy or difficult has your journey been?

In India, there is a gender bias and there is a bias against people who are not in government institutions. Gender bias also exists within the government institutions. The mindset is that serious research is only happening in the government sector. Private institutes and organisations are treated like second-tier and viewed with a degree of suspicion. This is something that has been institutionalised in the country.

If you could tell us about the cadre of young clinical translational medicine researchers that you are training and the role they can play in developing countries?

When I was about 45 years old, somebody asked me to define what success was for me? I said that if I can leave five people, who can do what I can do, then I have achieved everything I had wanted to achieve.

I trained in the UK and US for one year each. This was hugely empowering as people recognised that I was smart and capable and as good, if not better. In India, to praise is very rare. When you praise, you are deferential of people that you see as better than you in the pecking order, but not praise juniors who have done a great job. I returned to Vellore after training in the best scientific institutions of the world and with collaborations that would help us to grow even more. I wanted to make a difference but didn’t realise how difficult that was going to be. I had to figure out how to overcome various barriers – gender bias, hierarchal bias and class differences.

I have been mentoring, supporting but allowing students to grow and learn to tackle problems on their own. Our model, which has not been used before, is to take strong field epidemiology, back it with the best in lab testing with really robust systems for investigations.

Continue Reading on SciDev.Net

© Copyright Neena Bhandari. All rights reserved. Republication, copying or using information from neenabhandari.com content is expressly prohibited without the permission of the writer and the media outlet syndicating or publishing the article.

this means there can be many more vaccines if funding happens for research