By Neena Bhandari

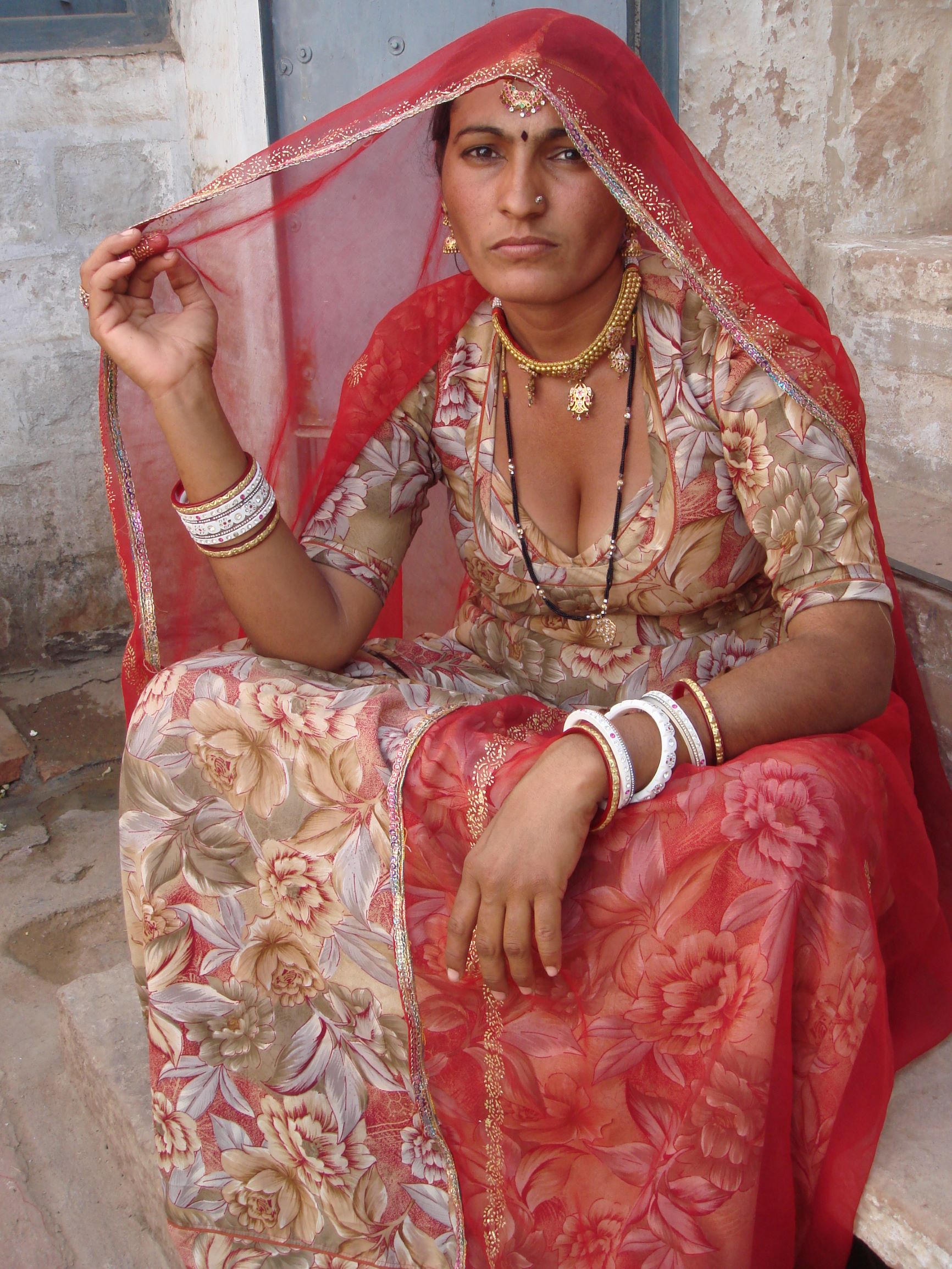

Jhakaron ki Dhani (Jodhpur, Rajasthan) 11.02.2012: In the dusty village of Jhakaron ki Dhani, 25 km from Jodhpur in western Rajasthan, early marriage and early motherhood are not uncommon. Shamu Meghwal was married at the age of 13 and her first baby was born at 15. At 25, she is the mother of four kids and has just lost her husband. Visibly anaemic, she epitomises the many young women in her community experiencing weakness, back and abdominal pain.

It is estimated that more than half of all married women in India are anaemic and one-third of them are malnourished (have a body index below normal). “These women are already at a lower health level when they get pregnant. They don’t receive proper nutrition, especially vital during pregnancy. This makes them anaemic resulting in long-term consequences on their health”, says Dr Kanta Tiwari, a known gynaecologist, who has been working in Jodhpur and surrounding areas for the past 41 years.

Only 46.6 per cent of mothers in India receive iron and folic acid for at least 100 days during pregnancy. “Even the protein intake is low in our village women here as they seldom have pulses/lentils. Among fruits, papaya is preferred. They also like Ber or Indian jujube (Ziziphus mauritiana) grown in abundance on the farms and occasionally pomegranate or guava”, says Dr Tiwari.

Some of these arid fruits and vegetables growing wild on the barren land provide food and nutrition security to the natives. Ber (Ziziphus mauritiana) is one such hardy minor fruit crop that is not only delicious but rich in Vitamin C.

Today, Shamu and her sisters-in-law are sharing a thali (plate) of raab (grounded bajra cooked in buttermilk), moth beans vegetable and bajre ki roti (millet flatbread), a common daily meal in most homes here. Depending on the income, the meal could comprise more seasonal vegetables like cauliflower, cabbage, onions or halwa (porridge) made of wheat flour, ghee and jaggery or churma made by crushing wheat chappatis, ghee and sugar.

The main crops grown in Jhakharon ki Dhani, which spreads across 852 hectares in Narva Panchayat of Jodhpur district, are millet, wheat, sorghum, moong, moth beans, cumin, chillies and seasonal vegetables. Agriculture and animal husbandry are the chief source of income with the number of cattle is estimated at 1464. Close proximity to the city has resulted in the village having a middle school and access to electricity, water, telephone and roads and some of the villagers gaining employment in nearby sandstone mines and the government.

But average age of marriage in Rajasthan is 17 years even though the legal marriageable age for girls in India is 18 years. Shamu’s younger sister-in-law, Bhagwati, 22, was married at 13 and has two small kids. She regularly has white discharge and often feels dizzy. Her older sister-in-law, Santosh, was married at 17 and has three children. Her second pregnancy resulted in a stillborn.

Most of these women give birth at home with the help of a midwife and resume sweeping, washing and other household chores within a week of childbirth. Many even begin toiling the fields in the harsh climatic conditions of the Thar desert. In India, only 47 per cent of women are likely to have an institutional delivery and 53 per cent had their births assisted by a skilled birth attendant.

Given that only about half of new mothers get antenatal care from a health professional, and only about one in three receive postnatal care within the first two weeks of giving birth, it is not surprising that India contributes to about a quarter of all global maternal deaths.

Each year over half a million women die of pregnancy related causes worldwide and 99 per cent of these occur in developing countries. The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in India is 254 per 100,000 live births according to Sample Registration System (SRS) Report for 2004-2006. MMR has a direct impact on infant mortality. Babies whose mothers die during the first six weeks of their lives are far more likely to die in the first two years of life than babies whose mothers survive.

Chuki Devi, 45, who was married at the age of 17, is amongst a handful of women to deliver her four kids in a hospital. Mohani Devi, 30, also had a caesarean section in a Jodhpur hospital. Breastfeeding her two-year-old she says, “I have a 10-year-old and then had an abortion so the family decided to have a hospital birth for my second child. My mother-in-law allowed me to rest for two months”.

But her sister-in-law, Chanani Devi, 35, who had her four kids at home resumed work soon after and now suffers from regular back pain.

Their mother-in-law, Sua Devi, 72, supervised her daughters’-in-law diet during pregnancy and after delivery. For the first seven to 10 days after giving birth, the woman is not given any milk. In most homes, the woman is given a fairly large sized laddoo made of wheat flour, ghee, almonds and other dry fruits, jaggery, sonth (dried ginger powder), ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi) and gond (edible gum) twice a day for about a month-and-a-half after delivery.

“The laddoo, which can weigh about 200 gm, is a rich source of calcium, iron, vitamins and proteins. For a few days, the new mother is also fed turmeric, which has antiseptic properties, heated in ghee. Mostly, new mothers eat bajre ki roti with vegetables and sometimes pulses/lentils or porridge made of wheat or millet for lunch”, says Dr Tiwari.

Munni Devi, 35, was married at the age of 10 and had the first of her four children at 15. She can only afford two meals a day, just enough milk for tea, and pulses/lentils once a week. Her daughter, who was also married early, has had twins at the age of 20.

“Normal rural woman needs 2200 kcal of energy per day. During early motherhood an extra 500 kcal is needed daily. Infant mortality rate is almost 50 per cent during the first month. It is due to combined effects of biological, economical and socio-cultural factors. Biological factors include low birth weight, early maternal age and interval between births. Socio-cultural factors include illiteracy, indigenous bias and poor environmental sanitation”, says Dr Anju Saluja, Consultant Radiologist at Manidhari hospital and Maloo Neurology Centre in Jodhpur.

Malnutrition is said to be an underlying cause for about one third of all deaths in childhood. Eight Indian states – Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Gujarat and Assam – contribute to 75 per cent of infant mortality. In 2008, the IMR was 53 per 1,000 live births. The neonatal mortality rate stands at 35 per 1,000 live births, and contributes to 65 per cent of all deaths in the first year of life. As many as 56 per cent of all newborn deaths occur in the five states of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh.

“High infant mortality is because of low birth weight babies, premature babies and deliveries conducted in houses by immature midwives who pay little attention to hygiene and asepsis. The babies do not have medical examination. Moreover, women often end up with torn muscles while giving birth, which results in prolapse and/or postpartum haemorrhage leading to anaemia later on. The women do not get routine check-up during pregnancy. Hence, any existing problems worsen after delivery thereby putting the life of the mother in jeopardy”, says Dr Tiwari, who regularly treats rural patients.

About half of the total maternal deaths in India occur because of haemorrhage and sepsis. Dr Pratibha Sharma, a practicing gynaecologist settled in Jodhpur for nearly 16 years, runs her own 12- bedded nursing home. While in her practice, she doesn’t encounter early motherhood problems as most of her patients are urban women, Dr Sharma says, “One does get these cases, where the woman is anaemic, has a poor built, narrow pelvis, has had early miscarriage or would tend to go into postpartum haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion”.

A large number of maternal deaths could be prevented through safe deliveries and adequate maternal care. “With increasing girl education, early motherhood age is now between 20 and 22 years, earlier it used to be between 16 and 18 years”, says Dr Tiwari.

Literacy is 507 in Jhakaron ki Dhani, which has a population of 1665. Chuki Jhakhar is one of the young generation of girls appearing for her Class XII exams, bucking the traditional early marriage trend in the village.

Empowering rural women through education, employment, easy access to health care and sensitising them about the importance of institutional deliveries could go a long way in preventing infant and maternal deaths and putting India on the path to meeting the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goal targets for maternal mortality ratio, infant mortality rate and the total fertility rate.

© Copyright Neena Bhandari. All rights reserved. Republication, copying or using information from neenabhandari.com content is expressly prohibited without the permission of the writer and the media outlet syndicating or publishing the article.