By Neena Bhandari

Sydney, 24.07.2020 (IPS): Sixteen-year-old Suhana Khan had just completed her grade 10 exams in March, when India imposed a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown. Since then, she has been spending her mornings and evenings doing household chores, from cooking and cleaning to fetching drinking water from the tube well.

“I am really missing school. Nearly half the year has gone and we have no books and no teachers to teach. We don’t know if and when we will be able to resume our studies,” Khan, from Kesharpur village in the western Indian state of Rajasthan, told IPS. The disappointment is palpable in her voice. While teachers at the local government school are supposed to conduct online classes, most of the 350 households in the village have only one mobile phone with internet connectivity, which male members in the family take to work.

School closures are putting young girls at risk of early marriage, unintended pregnancies and female genital mutilation (FGM). A recent analysis has revealed that if the lockdown continues for six months, the disruptions in preventive programmes may result in an additional 13 million child marriages, seven million unintended pregnancies and two million cases of female genital mutilation between now and 2030.

School closures are putting young girls at risk of early marriage, unintended pregnancies and female genital mutilation (FGM). A recent analysis has revealed that if the lockdown continues for six months, the disruptions in preventive programmes may result in an additional 13 million child marriages, seven million unintended pregnancies and two million cases of FGM between now and 2030.

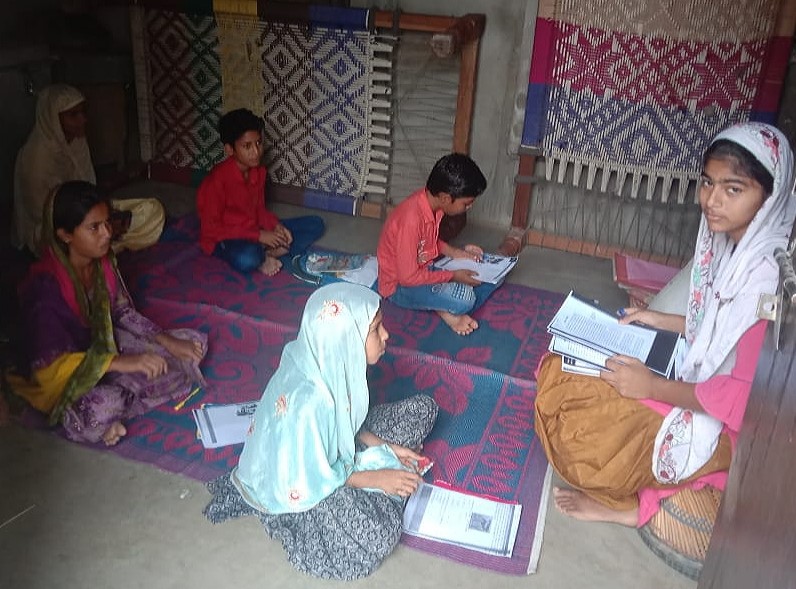

Khan has been fortunate to find work as a volunteer teacher with a local community based Non-Government Organisation, Bodh Shiksha Samiti. She teaches 11 children from her extended family for two hours daily in her own home.

“I wish there was someone to teach me too. I am desperate to continue my education and become a police officer so I am able to protect myself and other girls and women. We can’t step out of our homes after sunset. Every day, we hear of girls being abused,” she told IPS.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, the most progressive blueprint ever for advancing women’s rights and gender equality. It was supposed to have been a ground-breaking year for gender equality, but the novel coronavirus pandemic has instead widened inequalities for girls and women across every sphere – from education and health to employment and security. It has increased women’s unpaid workload and aggravated the risk of domestic violence.

Gabriela Cercós, 24, from Barueri, a municipality in Brazil’s São Paulo state, told IPS, “Women, who work from home are overburdened with housework, home schooling and looking after their children. In isolation, domestic violence has grown. Recently my close friend was assaulted, but she didn’t report the incident because she has a child and she can’t afford to be a single mother.”

As COVID-19 cases spiral, lockdowns are being extended, further isolating women living with abusive, controlling and violent partners. Civil society organisations are reporting an escalation in calls for help to domestic violence helplines and shelters across the world. But for every call for help, there are several others who are unable to seek support.

Globally 243 million girls and women (aged 15-49 years) have been subjected to sexual and/or physical violence perpetrated by an intimate partner in the past 12 months. Yet, nearly 50 countries have no laws that specifically protect women from such violence. The global cost of public, private and social violence against women and girls is estimated at approximately two percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) or $1.5 trillion. As security, health and money worries heighten, and the stress is compounded by cramped and confined living conditions, these numbers will soar, according to United Nations Women.

“Before COVID-19, we already knew that every country in the world would need to speed up progress to achieve gender equality by 2030. And we also know that disease outbreak affects women and men differently and exacerbates gender inequalities. That’s why to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and have a strong response and recovery to COVID-19, we must apply a gender lens in order to address the unique needs of girls and women, and leverage their unique expertise. Without this gender lens, we can’t truly ‘Build Back Better,’” Susan Papp, Women Deliver’s managing director for Policy and Advocacy, told IPS.

Women Deliver, an international organisation advocating around the world for gender equality and the health and rights of girls and women, is powering the Deliver for Good campaign, an evidence-based advocacy campaign that calls for better policies, programming, and financial investments in girls and women.

Essential maternal healthcare and family planning needs of girls and women have also been adversely impacted by reallocation of resources to contain the pandemic.

“The impact of COVID-19 across Africa on women, girls and youth in particular has been immense. The pandemic closed more than 1,400 service delivery points across IPPF’s member countries, including nearly 450 mobile clinics, which are vital to reach rural populations, and in humanitarian settings so often poor and underserved,” International Planned Parenthood Federation’s (IPPF) Africa Regional Director Marie-Evelyne Pétrus-Barry told IPS. IPPF is one of some 400 organisations and diverse partners that have joined the Deliver for Good campaign by committing to deliver for girls and women.

“Twenty of our African member associations reported shortages of sexual and reproductive health commodities within weeks of COVID-19 appearing. We’re now seeing the impact on our ability to deliver services, despite the very best efforts of our members to adapt to new ways of working.

“The number of services delivered to young clients in Benin between March and May fell by more than 50 percent compared with the same time last year. In Uganda the fall was 47 percent. These are devastating figures, and the impact on women, girls and youth will be have a very negative impact on the development, livelihood and human rights of African women, girls and youth,” Pétrus-Barry added.

Women are primary caregivers, nurturing their own families, and they are also serving as frontline responders in the health and service sectors. Globally, women make up 70 percent of the health workforce – nurses, midwives and community health workers. They also comprise the majority of staff in health facility services, such as cleaning, laundry and catering.

The pandemic has compounded the economic woes of women and girls, who generally earn less, work in insecure informal jobs and have little savings. Many women work in market or street vending, depending on public spaces and social interactions, which have now been restricted to prevent the spread of coronavirus. Almost 510 million or 40 percent of all employed women globally work in the four economic sectors – accommodation, food, sales and manufacturing – worst affected by the pandemic.

Cercós, who worked in hospitality at one of the international hotel chains earning a monthly income of BRL 2200 ($ 412) before the pandemic, is now on unemployment insurance. She’s just received the first of four instalments of BRL 1700 ($ 319) each.

“It is very difficult to get a job now. I have been having anxiety attacks. I am afraid to leave home and I am trying not to sink into depression. Some days are harder than others and the news doesn’t help,” she said.

This year, some 49 million extra people may fall into extreme poverty due to the COVID-19 crisis. In June, at the launch of the policy brief on food security, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres’ warned that the number of people who are acutely food or nutrition insecure will rapidly expand. He is urging governments to put gender equality at the centre of their recovery efforts.

Gerda Verburg, Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement coordinator and U.N. Assistant Secretary-General, noted that gender equality (SDG 5), good nutrition and zero hunger (SDG 2) are intrinsically linked. SUN is also a partner organisation for the Deliver for Good campaign, prioritising action and investments for girls and women.

“Before the COVID-19 pandemic reared its head, progress was stalling in these areas, alongside needed climate action. Although the impacts of the coronavirus on women’s and girls’ nutrition and food security are yet to be seen, there is no doubt that the loss of livelihoods and food system disruptions – disproportionally affecting women and the future perspectives of young women – will push countries even further from reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and ensuring a more equal world, free from hunger and malnutrition in all its forms,” Verburg told IPS.

© Copyright Neena Bhandari. All rights reserved. Republication, copying or using information from neenabhandari.com content is expressly prohibited without the permission of the writer and the media outlet syndicating or publishing the article.