By Neena Bhandari

Sydney, 07.11.2007: Nestling amidst the unkempt undergrowth of native shrubs, a haven for Rainbow lorikeets, kookaburras, bush rats and possums, Ian De Mellow’s home in the Sydney suburb of Wahroonga has kept alive his memories of a childhood spent in a Delhi bungalow with sprawling gardens.

“When you live in Australia for some years, as in India, the land itself permeates your soul”, says De Mellow, who arrived on the shores of Sydney in 1948 at the age of 13 with his mother and half-sister. His father, whose career as a superintending engineer in the central Public Works Department was bluntly nipped with all senior posts in independent India going to Indians, joined them four years later.

“There was a tremendous sense of betrayal and disillusionment with the British Raj”, he says. “My mother was part of the secret committee for air evacuation of Europeans, in case the post-partition riots spilled over to consume the European population”.

After three centuries, in August 1947, the British finally left India, dividing the subcontinent into two sovereign nations – India and Pakistan. The partition of the subcontinent, and the riots and bloodshed that ensued, left a strong impression on De Mellow’s young mind.

Some Anglo-Indian families, like De Mellow’s, chose to carve their new home in Australia – the last bastion of the Anglo-Saxon Empire, joining the thousands of other post Second World War immigrants.

“The passage to Australia was long and arduous. Coming here, reversed our whole understanding of the colonial history and provided a fresh perspective on the British Raj”, recalls De Mellow. “My mother could only afford boarding house accommodation. She was unable to even make tea as we always had servants in India”.

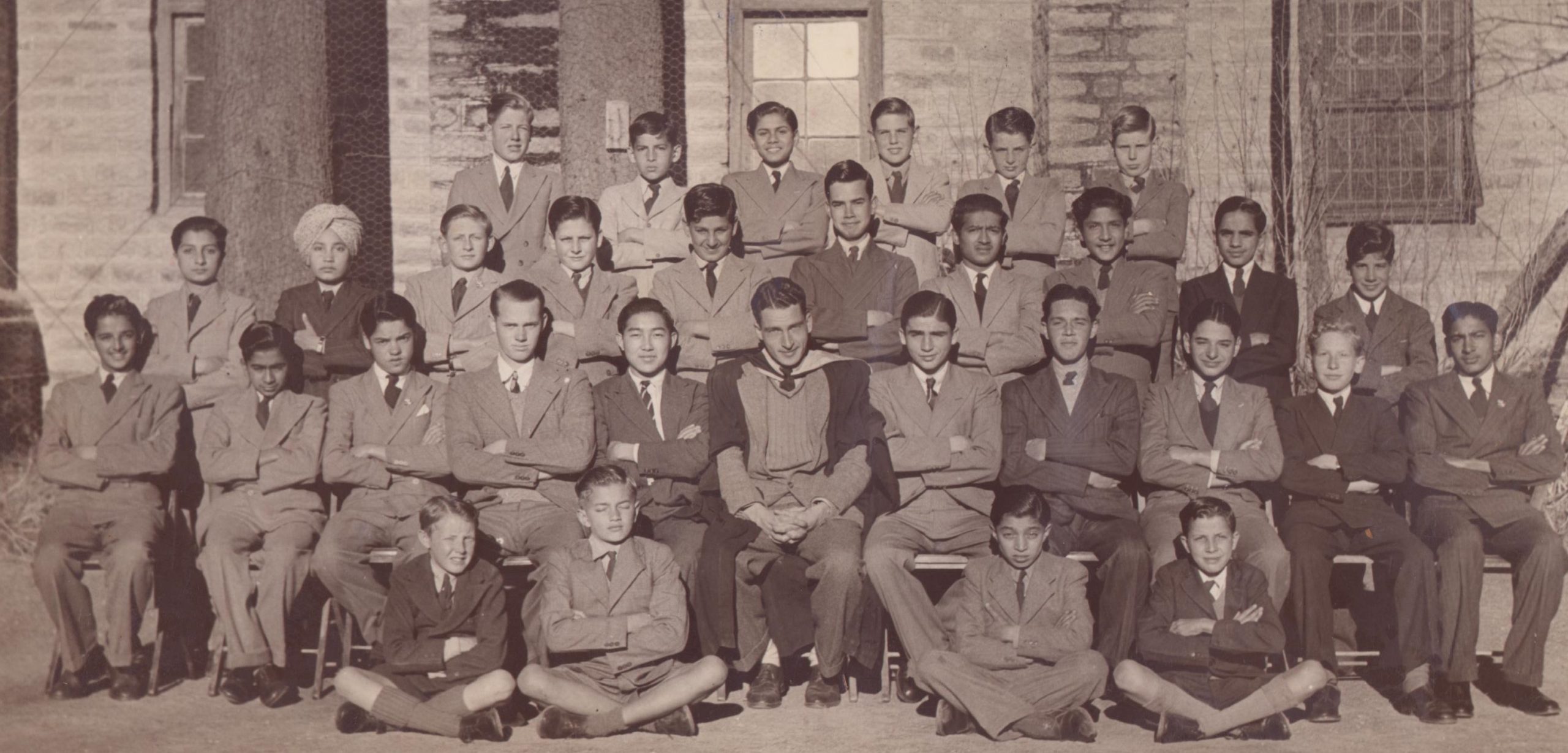

He remembers tasting his first tomato and the hot bowls of porridge at his new Sydney school, which was a far cry from the sumptuous breakfasts at the Bishop Cotton School in Shimla (Himachal Pradesh).

“I was an object of curiosity in school and was nicknamed `Yogi’ – that is the image Australians had of someone from India in those days. The food was stodgy, real curry powder was sold across the chemist’s counter like some potentially toxic medication”, adds De Mellow, who is the nephew of the famous All India Radio broadcaster, Melville De Mellow.

He feels fortunate to have been born in a magical country and now living in a city that abounds in natural beauty. “A 30-metre-high native Peppermint Gum (Eucalyptus radiata) tree is our pride and joy today. On a hot day or after rains, it emits a distinctive scent, which reminds me of the fragrance of `Raat ki rani’ (Cestrum nocturnum) flowers that filled the balmy Delhi nights”, reminiscences De Mellow.

His favourite pastime is to relate anecdotes from his boyhood days in India — of flying kites and riding a bicycle through the canopy of trees shading the Delhi streets – to his grandchildren.

Australia has been a generous and welcoming land for the 50,000-odd Anglo-Indians and their descendants, who have made it their home since 1947.

Being part of the Commonwealth, fluency in English, parliamentary democracy and the passion for cricket has proved the transition to a new land much easier for the Indian Diaspora, which stands at 234,720, according to the 2006 Census. [The number has grown to 455,389, according to the 2016 Census.]

It is believed that the first Indians came to Australia in 1770 aboard English Lieutenant James Cook’s ship, HMS Endeavour. The British brought Indians to run camel trains for transporting goods, water and mail from the Australian cities to the central region, which had no rail or roads then. They were called Afghans, who played a vital role in opening the remote outback of Australia. According to some research estimates, between late 1880s and 1920s, there were about 2000 to 6000 cameleers.

Then came hawkers and labourers, largely from Punjab, who serviced the remote farming communities and sheep stations by supplying merchandise on their horse-drawn carts or worked on the mines.

Further Indian immigration, except for the Anglo-Celtics, was restricted following the implementation of the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act, popularly known as the White Australia Policy.

In 1972, the Eighth Nizam of Hyderabad, Mukkaram Jah, came to Australia to visit an old friend from Cambridge, who was a country doctor near Perth. “He fell in love with the outback as it was as far removed from the incestuous atmosphere of Hyderabad, where his own father was taking him to court”, says Australian journalist John Zubrzycki, who has provided the first complete account of the Nizam’s intriguing life and times in his book, The Last Nizam.

It was not until 1975, when the Racial Discrimination Act abolished the `Whites Only’ policy, that a broader range of Indian professionals — doctors, teachers, engineers, bankers – began to settle here. The 1990s saw a large number of Indian computer professionals make Sydney and Melbourne home.

During this time, many Indian origin people from Fiji also migrated to Australia following the military coups of 1987 and 2000, thereby changing the demographics of the Australian-Indian community. Many Fijian-Indians, who were business oriented, established small and big enterprises across the country.

Indians in Australia hail not only from the sub-continent, but from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, Fiji, South Africa, Mauritius, the United Kingdom and other European countries.

The Indian community punches far above its weight even though only one percent of the 25 million Indian Diaspora spread across the world, is in Australia.

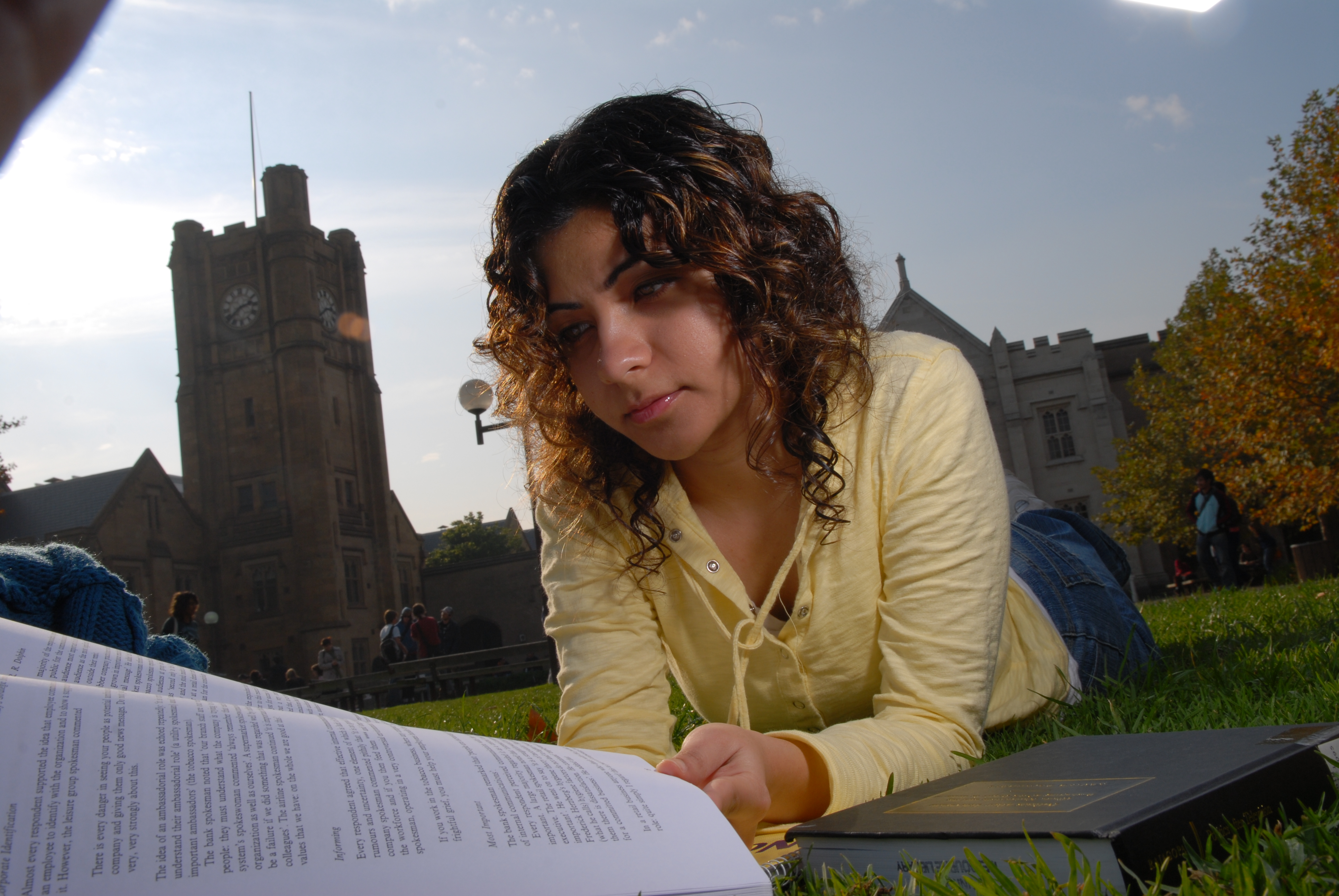

As Robin Jeffrey, professor of politics at Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra says, “A generation ago if you attended an Indian function, it was a question of whether the doctor on your right was a psychiatrist or a surgeon; the doctor on your left would be a General Practitioner (GP). In short, it was a very upper-middle-class set of people. Today, Indian students are the face of India in Australia, and there is a much larger Indian working-class component”.

Agrees Australia’s leading social scientist Bob Birrell, director of the Centre for Population and Urban Research at Monash University in Melbourne. “The Indian community holds a respected place in Australian society. In recent years, overseas students are increasingly being drawn from a different segment of Indian society than the earlier stream. They often come from regional or rural backgrounds, do not speak English well and end up working in the hospitality and service industries rather than as professionals”.

According to the 2006 Census, the Indian Diaspora is well educated, largely employed and earning more than the median individual weekly income. The main languages spoken at home were English (34.4 per cent), Hindi (19.9 per cent) and Punjabi (10.3 per cent); and the major religious affiliations were Hinduism (64,970 persons), Catholic (34,510 persons) and Sikhism (16,470 persons).

Interestingly, while there was only one Hindu amongst the 36,000 or so residents in the 1828 census of the New South Wales (NSW) state, Hinduism has become one of the fastest growing religions in Australia more than doubling to 150,000 since 1996.

Australia’s first Hindu stockman, Ramdial, was born most probably in 1788 and arrived in Australia aboard the ship Mary in 1818 with Sophia Browne, the wife of his employer William Merchant Browne, and three of Browne’s children from Calcutta (Kolkata).

There is documented evidence to suggest that Browne brought up to 40 Indian workers to Australia during the early 1800’s. Many of them were repatriated to India at the end of their service contract.

“At the time the census was taken, Ramdial was the only ‘Free’ person working at the Browne’s farm in the Sydney suburb of Cabramatta, the other nine workers were all convicts,” says Brad Argent, a spokesperson for Ancestry, the world’s biggest provider of family history data, who was amazed to find the only “Hindoo” entry in the household section of the census form.

The number of Hindus in Australia comprise 0.7 per cent of the total population. During the last decade, several Hindu temples have been consecrated in all major capital cities of Australia, but the Sri Venkateswara Temple in Helensburg, an hour’s drive south of Sydney, is a landmark in the history of Hindu immigration to Australia.

The number of Hindus in Australia comprise 0.7 per cent of the total population. During the last decade, several Hindu temples have been consecrated in all major capital cities of Australia, but the Sri Venkateswara Temple in Helensburg, an hour’s drive south of Sydney, is a landmark in the history of Hindu immigration to Australia.

Built in the South Indian temple architectural style, the foundation for the temple was laid in 1978. The original temple was consecrated in June 1985 and since then the Shiva Temple complex; mandapams (halls) and rajagopurams (towers) have been added.

Likened to the famous Tirupati temple in India, the temple’s location atop a hill surrounded by forests and only a few km from the Pacific Ocean, is unique. For the larger Indian community, the temple complex provides a religious and cultural focus and a sense of achievement, representing their efforts to link history, religious beliefs and tradition with their future in Australia.

Today, Sydney’s cultural calendar includes the annual Diwali Fair, Holi Mahotsav and the Australia India Friendship fair. The Friendship Fair, which attracted only 250 people in 1994, has grown manifold to become one of Australia’s largest cultural events, next only to the Chinese New Year. Organised by the United India Association (UIA), the apex body representing 18 Indian community organisations in the country, the fair is living up to its commitment of bonding global cultures in the pursuit of Vasudaiva Kutumbakam.

Second generation Indians and the changing nature of Indian migrants has influenced the way festivals and weddings are being celebrated today. Shivali English, who came to Sydney at the age of 10 says, “Despite growing up with mainstream Australians, I had assumed that I would marry an Indian until I met Glenn at 19”.

Her parents, Shankar and Shakuntala Dhar, were open to the idea of her marrying an Australian of Irish descent, but they were keen to have the traditional “saat phere” wedding before the Christian ceremony.

“While the Indian wedding was bursting with colour, excitement, exhaustion and where I had no control, the Christian ceremony was black and white, casual with the iconic Opera House and Botanical Gardens in the backdrop and myself in total control”, says Shivali, who had dreamt of a white fairy tale wedding ever since she met Glenn 10 years ago.

“While the Indian wedding was bursting with colour, excitement, exhaustion and where I had no control, the Christian ceremony was black and white, casual with the iconic Opera House and Botanical Gardens in the backdrop and myself in total control”, says Shivali, who had dreamt of a white fairy tale wedding ever since she met Glenn 10 years ago.

In 2007, 30 per cent of marriages were between people hailing from different countries of birth, enriching the diversity of Australian multicultural fabric. It is worth noting that Indian brides have become one of the largest and fastest growing groups leading the migration surge Down Under.

In 2007, as many as 2,782 Indian brides were sponsored by India-born men and 496 Indian husbands were sponsored by their wives, a six-time increase compared to 11 years ago when only 434 Indian brides and 149 Indian husbands were sponsored by their spouses.

Paramjeet Singh, 23, had come to Australia two years ago on a student visa to do a hospitality course. He says, “Earlier this year, I returned home to Chandigarh to have an arranged marriage and now we are starting our life together here.”

The increase in Indian spouses reflects the trend whereby Indians have become the second largest group of skilled migrants and overseas students.

Indians, as the second largest cohort of overseas students, contribute significantly to Australia’s $14 billion education export industry. With 65,000 overseas Indian students enrolled in Australian educational institutions, universities are seeking research collaborations and student exchange programmes with India’s premier institutes.

“The time is ripe for major investment in Indian studies, including Indian languages, in Australia. With the sharp increase in commercial exchange between the two countries, there will be more demand for India-related courses and academic activity in Australia. The Australia-India Strategic Research Fund is a good beginning,” says Dr Raghbendra Jha, who migrated here with his family in January 2001 from Mumbai, where he was Senior Professor at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

The Asian Giants: India, China and Japan course at the ANU has attracted considerable interest in recent years. “Indians know a lot about Australia, but Australians don’t necessarily know enough about India”, says Jha, Executive Director at ANU’s Australia South Asia Research Centre, who has been supervising PhD dissertations on the Indian economy.

For the past eight years, Jha has been instrumental in bringing the Crème de la Crème of economics, politics and policy to deliver the K R Narayanan Lectures at the ANU. “It has helped raise the profile of India Down Under. We now have business scholarships for Indian overseas students. We were recently able to raise funds to appoint a post-doctoral fellow to research the social safety nets in India like the Public Distribution System and mid-day meal schemes”.

Young Indians are also helping strengthen the Australian economy with 15,865 professionals seeking permanent residence under the skilled migration programme during 2006-2007.

Many of the Indian origin migrants are gradually becoming active participants in the political process of their adopted country. Hobart-born Lisa Maria Singh, 36, has become perhaps the only Indian origin person to recently become a minister in Tasmania’s state parliament. Her grandfather, Ram Jati Singh, was a Member of the Fijian Parliament during the 1970s and her father migrated to Australia in the 1960s.

“It always takes time for a recently arrived ethnic group to enter politics. Often it is the second generation which takes this step, in part because they have wider connections and motivation to engage with the mainstream community”, says Birrell.

Unlike in many other countries, Indians have yet to achieve political prominence in Australia. “There has not been a large enough, long-enough-established Indian population to generate a politically active pool of people yet in Australia, unlike in Canada, the United States or the United Kingdom, where a large number of Indian-origin people go back at least three generations”, says Jeffrey.

With increased travel between the two countries for leisure and business, the people-to-people connections are dispelling myths and misconceptions. Indians are coming `Walkabout’ and many more Australians are soaking up the `Incredible India’ experience.

Indian visitors to Australia are expected to increase from 95,000 in 2007 to 440,000 in 2017, an average annual growth of 16.5 per cent. Similarly, last year, nearly 130,000 Australians travelled to India.

Some credit for it must go to Bollywood films. India-Australia film links can be traced to the tall, blue-eyed, blonde girl, best known for portraying the masked, cloaked adventuress `Hunterwali’. The unconventional stunt queen of the 1930s and 1940s was Perth-born Mary Evans or our own `Fearless Nadia’.

After appearing on stage and in a circus in India, Mary was “discovered” in Bombay in 1935 by brothers J.B.H. and Homi Wadia, who ran Wadia Movietone. She acted in more than 55 movies during a career spanning 27 years, attaining an unmatched level of popularity in India.

Bollywood is today cashing on the Australian appeal by incorporating aspects of Australian lifestyle. Initially, Australian locations were used as the setting for fantasy song-and-dance sequences or to demonstrate the contrast between foreign and Indian values, but now they are becoming more important to the plot of Bollywood films. In 2005, Salaam Namaste became the first film to be entirely shot in Australia followed by Hey Babyy, Chak De! India, Singh is Kinng and others.

From films to clothes and cuisine, culture and commerce, everything Indian is catching Australians’ fancy. Indian migrants are transforming the Australian way of life even as iconic Australian wines to vegemite and sunscreen become the new craze for Indians back home.

Delhi-born vigneron, Paramdeep Ghumman, has carved a niche with his Nazaaray of boutique wines in the southernmost shire of Flinders located on the Mornington Peninsula in the state of Victoria. Growing up in a teetotaler family, he hadn’t sipped any alcohol until the age of 22.

“I acquired the taste for wine after coming to Australia,” says Ghumman, a computer software engineer turned professional wine grower and maker, who migrated to Australia in 1981 from Calcutta (Kolkatta).

Since 1999, the 57-year-old has won many accolades for his boutique wines. His Pinot Gris 2007 was awarded the Silver Medal at the Victoria regional showcase in Melbourne. Nazaaray’s cellar door is unique too, housed inside a 1930s railway carriage. The couple invites wine lovers for Table d’hote to join the family and workers for a traditional Indian lunch ranging from tandoori paranthas and tandoori chicken to the good old Indian street chaat experience.

The acceptance and appreciation of Indian food has undergone a sea change. “We have come a long way from what was once called the `curry powder’ food to providing fine dining experiences. Australians now even know about food from different regions of India”, says Surjit Singh Gujral, who has an 80 per cent committed Australian clientele at his two Sydney restaurants.

The Gujrals, who migrated here from Chandigarh in the mid-1970s, have been amongst the pioneers to introduce Indian cuisine to the Australian palate. His brother’s restaurant, Amars, was one of the first in Sydney.

“In the 1980s, Indians had limited money and wouldn’t spend to go out and eat Indian food. If at all, it was for Tandoori”, says Gujral, who offers a select menu of authentic dishes and insists on an open kitchen dining experience.

“People first eat with their eyes and then develop the taste,” says Gujral, who still cooks and provides apprenticeships for overseas Indian students doing cookery and hospitality courses. At least 25 chefs, who trained under him, have gone on to start their own restaurants.

A “very proud Australian-Indian”, he wants to promote closer links between the two countries through Indian food and exchanges of art, culture and music. He looks up to former Australian cricket captain, Steve Waugh, as a great ambassador for both countries.

Cricket does transcend borders and is a game passionately contested. Pune-born Lisa Sthalekar started playing cricket with her father at the age of five. Both enjoyed watching matches at the Sydney Cricket Ground and at nine years, she joined the West Pennant Hills Cricket Club in the Sydney suburb of Cherrybrook.

Cricket does transcend borders and is a game passionately contested. Pune-born Lisa Sthalekar started playing cricket with her father at the age of five. Both enjoyed watching matches at the Sydney Cricket Ground and at nine years, she joined the West Pennant Hills Cricket Club in the Sydney suburb of Cherrybrook.

“I was the only girl and bowled my first ball in the opposite direction! When the boys saw I had some ability with the bat and ball, they became very protective of me like big brothers,” recalls Lisa, who would hide her ponytail under the cap, but after a year of playing, one day the cap fell and the boys yelled “That bloke is a girl”!

The 28-year-old is today Australian Women’s cricket team’s vice-captain and has been twice named the Women’s International Cricketer of the Year. She is also the high-performance coach for all of the junior elite cricketers in the state of NSW. “In junior cricket, there are many girls from India and the sub-continent, China and other ethnic backgrounds”, she says.

It has never been easy to take sides in cricket for Australian-Indians. To use a cricket metaphor, the growing Indian diaspora is in for a long and successful Test innings in a country of open spaces, tropical climate, safe environs, quality lifestyle and creative opportunities, they now call home.

WOOLGOOLGA: The imposing white domes and minarets of the Guru Nanak Sikh temple stand tall as a gateway to the scenic beachside town of Woolgoolga. Resplendent with sub-tropical rainforests and farms rolling into the Pacific Ocean, it is almost midway on the long stretch of the Pacific Highway linking Sydney in the south to Brisbane in the north.

Woolgoolga or `Woopi’ to the locals has long been an oasis of rural Sikh culture in Australia. It was during the 1940s that the first Sikh settlers moved here from the sugarcane fields of northern Queensland to work as labourers on the banana plantations.

Amongst a group of 40 Indians, who came to north Queensland as agricultural labourers in 1885, was 80-year-old Teja Singh Grewal’s grandfather. His father followed suit many years later.

“In those days, only the men came here for work and the family stayed at home in India. I was 18, when my father decided to bring us to Australia in 1947”, says Grewal, who hails from Dhaliwal village in Punjab and is today a registered Minister of Sikh religion in Woolgoolga.

The landmark Guru Nanak Sikh Temple, built in 1970, and the smaller First Sikh Temple, built a year earlier, have become a hub for the old and young to come and offer prayers and participate in the langar or community dining experience.

“During the weekend, many tourists and mainstream Australians come and enjoy the langar with us”, says Grewal, who is also an authorised marriage celebrant.

The Sikhs represent about 25 per cent of the total population of Woolgoolga, comprising a blend of descendants of the original settlers and those who have migrated to join their extended family or marry within the community.

“About two per cent of the Sikhs are marrying Australians and 70 percent are marrying within Sikh families settled across Australia,” adds Grewal.

According to the 2006 Census, there were 4,356 persons residing in Woolgoolga’s urban centre localities with 80.5 percent persons born in Australia and 5.1 percent born in India. The most common language, other than English, was Punjabi with 9.7 percent of the population speaking Punjabi at home and following Sikhism.

Sikhs have been commended for their diligence and significant contribution to the local economy. Today, over 90 percent of Woolgoolga’s banana industry is owned and operated by Australians of Sikh ancestry.

“My four daughters and son help me in the plantations and we employ some casual labour”, says Paramjit Bhatti, whose grandfather migrated to Australia soon after the Second World War with his sons and continued to keep strong ties with the extended family and friends in their hometown, Namashahr in Punjab.

Many second and third generation migrants are enrolling in universities and moving to cities to work as professionals in various fields – from teaching and medicine to law and finance.

Sharon Singh, whose father had relocated to Woolgoolga from Queensland and purchased a banana farm in 1971, has been working in the recruitment industry for the past 21 years. The youngest of six siblings, Sharon was four-years-old when her family moved to Woolgoolga.

“We all worked on the farm. Men did the hard labour and women stayed in the shed and helped with packing bananas”, adds Sharon, who has ensured that her two children imbibe the best of Punjabi and Australian cultures.

During the southern autumn, Woolgoolga comes alive with Indian cuisine, music and dance for the annual Curryfest coinciding with Baisakhi, celebrating the town’s unique Sikh culture, religion and heritage that has enriched the cultural diversity of this “very Indian” town on Australia’s eastern seaboard.

Above text is from a chapter, `Nestling Down Under…and burgeoning’ written in 2007 for `At home in the world’ book published by Overseas Indian Facilitation Centre (OIFC).

© Copyright Neena Bhandari. All rights reserved. Republication, copying or using information from neenabhandari.com content is expressly prohibited without the permission of the writer and the media outlet syndicating or publishing the article.

Enjoyed learning about so many aspects of the Indian diaspora in Australia today. It is good to see how much more of an inclusive accepting community Australia has become since 1975.