By Neena Bhandari

Uluru, 05.09.2016 (Outlook India): Australia conjures images of sea and surf, but it is in the sun and sand of its Red Centre desert that I discover the country’s spiritual heart. Uluru [Ayers Rock] along with Kata Tjuta [The Olgas] have been part of the traditional belief system of Australia’s first people. The ochre-tinted inselberg stands tall in the vast arid landscape, linking the country’s indigenous Aboriginal past to our present and the future.

As the plane begins its descent to the Connellan Airport, a glimpse of Uluru’s famous silhouette evokes a sense of awe. The winter sun on the tarmac is comforting as unhurried passengers make their way into the small airport to a pleasant `Palya’ or welcome. A relief from the intense security screenings one has to endure at most airports in our post 9/11 world.

Aboriginal people have been living in this region for at least 22,000 years. To ensure the traditional owners of the land, the local Anangu Aboriginal community belonging to the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara tribes, and their culture is respected, visitor accommodation is located 20km away from the base of Uluru, in Yulara village. Tourist activities in this UNESCO World Heritage-listed Natural and Cultural site are managed by Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia, which offers the local community employment and training in sustainable ecotourism.

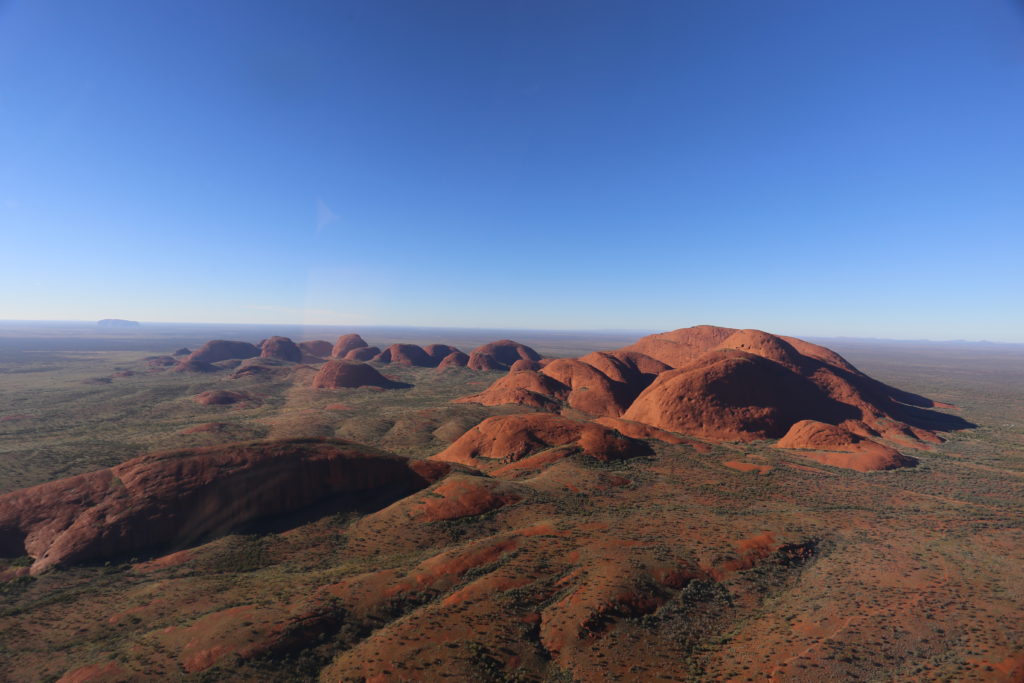

VIEW FROM 3500 FEET: A bird’s eye view of the landscape from 3500 feet above in a helicopter is mesmerising. Like most other visitors, I was aware of Uluru and Kata Tjuta, but I notice a third rock. “It is Mount Conner, also known as Attila, located on private land”, says our young Professional Helicopter Services pilot, Anika. “Many tourists our fooled by it so it is often referred to as `Fool-uru’.”

VIEW FROM 3500 FEET: A bird’s eye view of the landscape from 3500 feet above in a helicopter is mesmerising. Like most other visitors, I was aware of Uluru and Kata Tjuta, but I notice a third rock. “It is Mount Conner, also known as Attila, located on private land”, says our young Professional Helicopter Services pilot, Anika. “Many tourists our fooled by it so it is often referred to as `Fool-uru’.”

Mount Conner, Uluru and Kata Tjuta are situated along a straight line. While Mount Conner is a flat-topped, horseshoe-shaped 300-metre high inselberg, Uluru is 348 metres high with a much greater mass of rock hidden in the earth’s crust, and Kata Tjuta meaning ‘many heads’ is 546 metres high and made up of 36 conglomerate rock domes.

Nature in this part of Australia has been unforgiving, but has a distinct beauty. The 311,000 acre Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, which was returned to the local Aborigines in 1985 and who in turn granted the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service a 99-year lease on the park, is home to various species of mammals, including the red kangaroo and dingo; birds such as the Black-Breasted Buzzard and Spinifex Pigeon; and reptiles like the Great Desert Skink and Mulga Snake. Spiders, insects, ants and flies abound too.

FIELD OF LIGHT: At sunrise and sunset, a soft glow lights up the 50,000 solar-powered handcrafted light stems crowned with frosted-glass spheres in hues of white, blue, red, yellow. It is British artist, Bruce Munro’s Field of Light installation covering 49,000 square metre or nearly seven football fields, which will remain open until 31 March 2017. Munro wanted to create “an illuminated field of stems that, like the dormant seed in a dry desert, would burst into bloom at dusk with gentle rhythms of light under a blazing blanket of stars”. Indeed, a blink and in the still darkness of the outback sky, all one can see is a carpet of stars stretching as far as the eyes can see into the horizon. Traversing through the gleaming pathways amidst the monumental art phenomenon termed Tili wiru Tjuta Nyakutjaku [looking at lots of beautiful lights] in local Pitjantjatjara language, is pure magic.

MOVEMENT OF THE SUN: As the sun glides from east to west, Uluru wears shades of bright yellow, orange, ochre and red for which it is renowned. At dawn, the moon is still bright. Sarah, our guide from SEIT Outback, drives us to a vantage point on a deserted road overlooking Uluru. Within minutes she has laid breakfast in the boot of the 12-seater van. Guides in Australia not only share their knowledge and experience of the area, but invariably multi-task. The desert air is cold as we wait in anticipation for the first sunrays to illuminate the flat peak, gradually immersing the entire rock in sunlight. The surface oxidation of the sandstone rock’s iron content giving it the bright orange-red colour.

As we drive around Uluru’s 9.4 km base walk to the sacred Mutitjulu waterhole, Sarah tells us the Aboriginal Creation story of Liru (poisonous snake) and Kuniya (python). The smooth profile of the rock from afar is deceptive as up-close, one encounters numerous valleys, ridges, caves produced by vagaries of nature over millions of years.

The Evening sky is dramatic too, draped in crystal clear blue with streaks of turquoise, pink and mauve. Far away from the city lights of Sydney and Melbourne, as nightfalls Kim Yusuf, a Kiwi who migrated from Pakistan, takes us on a celestial journey. His laser beam moving from the Southern Cross, the Milky Way, to the signs of the zodiac and planets. To visitors from the northern hemisphere, he says, “Imagine the sky upside down in your mind’s eye”.

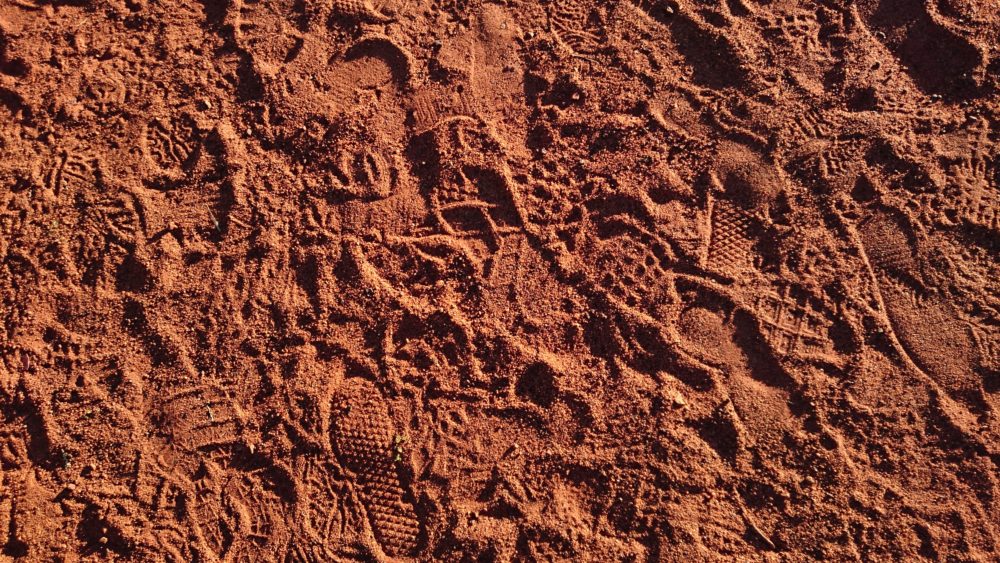

OUTBACK MARATHON: On the last Saturday of July each year, the Australian Outback Marathon attracts participants from nearly 25 countries. In its seventh year, nearly 500 people participated in one of the four categories – 42.2km marathon, 21.1km half marathon, 11km and 6km fun run/walk. It was Mari-Mar Walton, the founder of Travelling Fit, who started the event to allow runners to experience the red earth of Central Australia and showcase the region. Runners meander through flat graded sealed and unsealed bush roads, soft sand trails and small sand dunes, with stellar views of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. As an excited runner from Florida told me, “I have wanted to run a marathon in every continent. When this one popped up during my google search, I just took the challenge and it has been an exhilarating experience”.

LAST WORD: In the deafening silence of the sparsely populated desert, I hear spattering of Spanish, Mandarin, French and English accents from Canada and Scotland to India and South Africa. The red sand is imprinted with footprints, erased and reinscribed by new visitors each day, perhaps signifying the ephemeral nature of life and the resilience of the Aborigines who have survived through eons.

© Copyright Neena Bhandari. All rights reserved. Republication, copying or using information or photographs from neenabhandari.com content is expressly prohibited without the permission of the writer and the media outlet syndicating or publishing the article.